The recent New Yorker article, “How Dartmouth Became the Ivy League’s Switzerland,” argues that Dartmouth has not been singled out by Washington the way other Ivies have (at least so far) because its leadership has leaned into institutional neutrality and process-driven “dialogue.”

Specifically, in April 2025 President Sian Beilock did not sign a widely supported open letter defending higher ed from federal overreach (all other Ivy presidents did), arguing that Dartmouth should focus on action and self-reflection rather than “form letters.”

So, per the New Yorker, by avoiding collective statements and emphasizing neutrality, Dartmouth has escaped targeted federal sanctions that some peers faced — drawing praise from free-speech advocates and criticism from others who see the stance as naïve or tacitly accommodating.

That seems plausible. However, the real reasons for both Beilock’s independent stance and Dartmouth’s perceived immunity from U.S. government actions are the school’s rock-solid finances.

It’s the liquidity, stupid!

More than a year ago, in MPI’s annual endowment report, “A Private Equity Liquidity Squeeze by Any Other Name,” we assessed the looming liquidity crunch facing elite endowments — nearly a year before any threats of government funding cuts were on the horizon.

What followed was a perfect storm: a drought after several years of record-low PE distributions (typically used to fund capital calls); cuts in donations from prominent alumni frustrated by universities’ lack of response to antisemitic violence on campus; tariff-induced market volatility; and, on top of that, both real and perceived threats of losing billions in government funding. All of this prompted unprecedented debt issuance by cash-strapped schools, as well as sizable secondary sales of PE stakes by some (Harvard and Yale), while others explored these and additional options (beefing up lines of credit, large expense cuts, etc.).

Dartmouth, by contrast, didn’t even tap its line of credit, raised no debt in the 2024 fiscal year, and issued only $100 million of taxable commercial paper in FY25 — while other Ivies issued more than $8 billion in non-taxable and taxable bonds over the same two-year period. How is it possible that Dartmouth — despite a significant PE allocation ($3.2 billion as of FY24, or 36.6 percent of the portfolio, about the Ivy average of 36.8 percent) — was able to weather the storm?

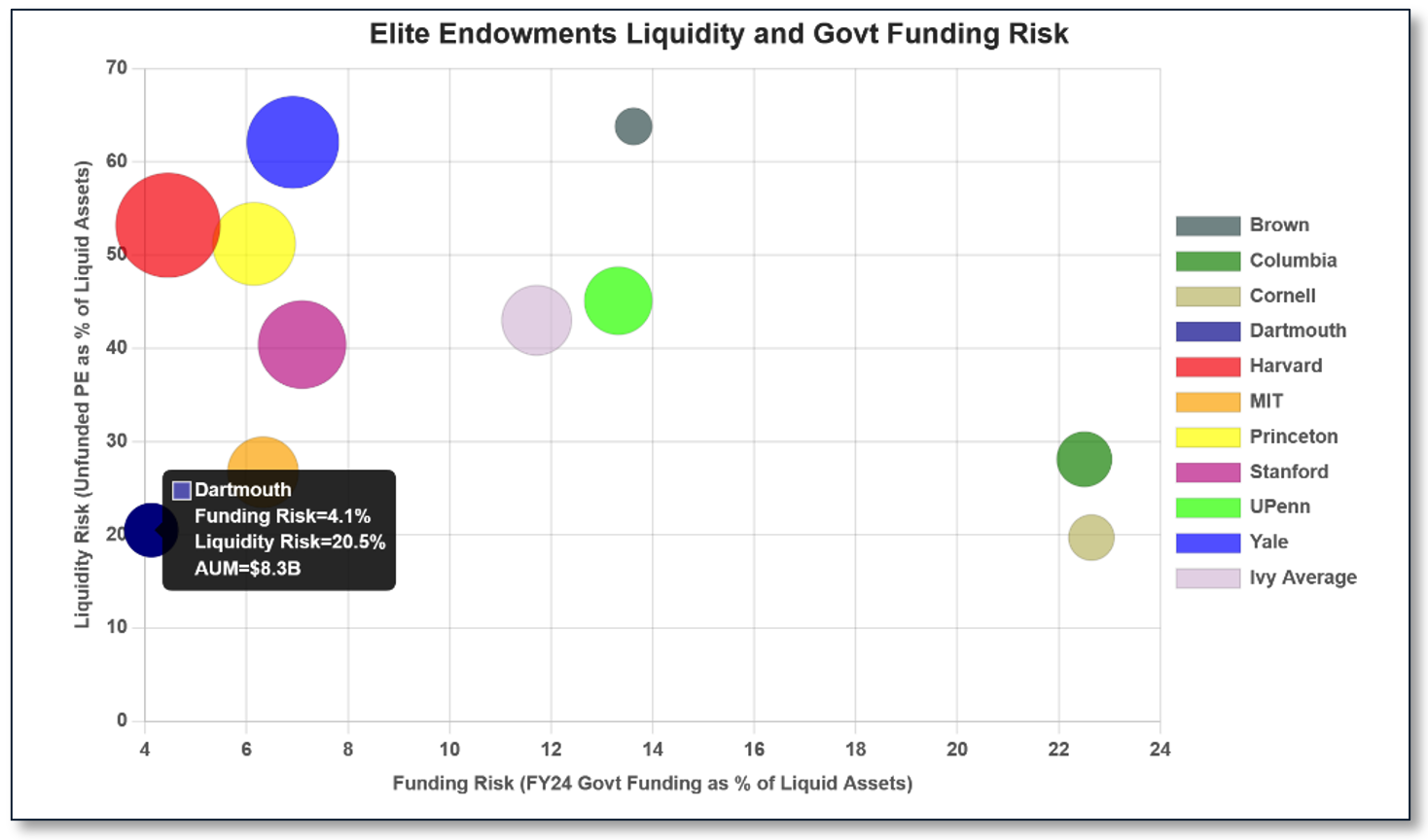

The answer is straightforward: According to the MPI Transparency Lab, Dartmouth’s endowment is highly resilient and relatively insulated from government-funding risk compared with peers. The diagram below shows liquidity risk (Y-axis), measured by the ratio of unfunded PE commitments to MPI-estimated liquid assets, and government funding risk (X-axis), measured by the ratio of FY24 government grants to liquid assets.

In today’s perfect storm, both risks matter. Schools need liquidity to fund GP capital calls and to plug gaps in research and on-campus operating budgets. These pressures compound; a school like UPenn — hardly the worst on either single axis — finds itself extremely stressed as liquidity demands stack up.

Dartmouth, however, sits in a unique spot in the lower-left corner of the diagram: It has the lowest liquidity risk at 20.5 percent. For comparison, the average Ivy’s liquidity risk is roughly twice that, and Yale’s is about three times higher. Brown, Yale, and Harvard exhibit some of the highest liquidity risk; it was therefore unsurprising that Yale and Harvard sold significant PE stakes in the secondary market and that multiple schools raised billions in debt. For instance, the $800 million borrowed by Brown (the smallest Ivy) so far this calendar year is akin to Yale or Harvard raising about $5 billion, a telling indicator of financial stress.

Looking to the right side of the diagram, Columbia and Cornell face a different form of liquidity stress: Their operating budgets rely heavily on government funding (X-axis) relative to other Ivies. Combined with the low liquidity of their endowments, this reliance makes them extremely vulnerable to funding cuts and places them in the same liquidity-crunch “league” as Yale and Harvard.

Dartmouth, by contrast, has the lowest government funding cut-off risk among the ten elite schools we track. Its endowment is one of the most liquid (liquid assets, per MPI estimates, comprise 36 percent of the endowment), and the school received the smallest amount of U.S. government grants in FY24: $143 million.

But that’s only part of the story.

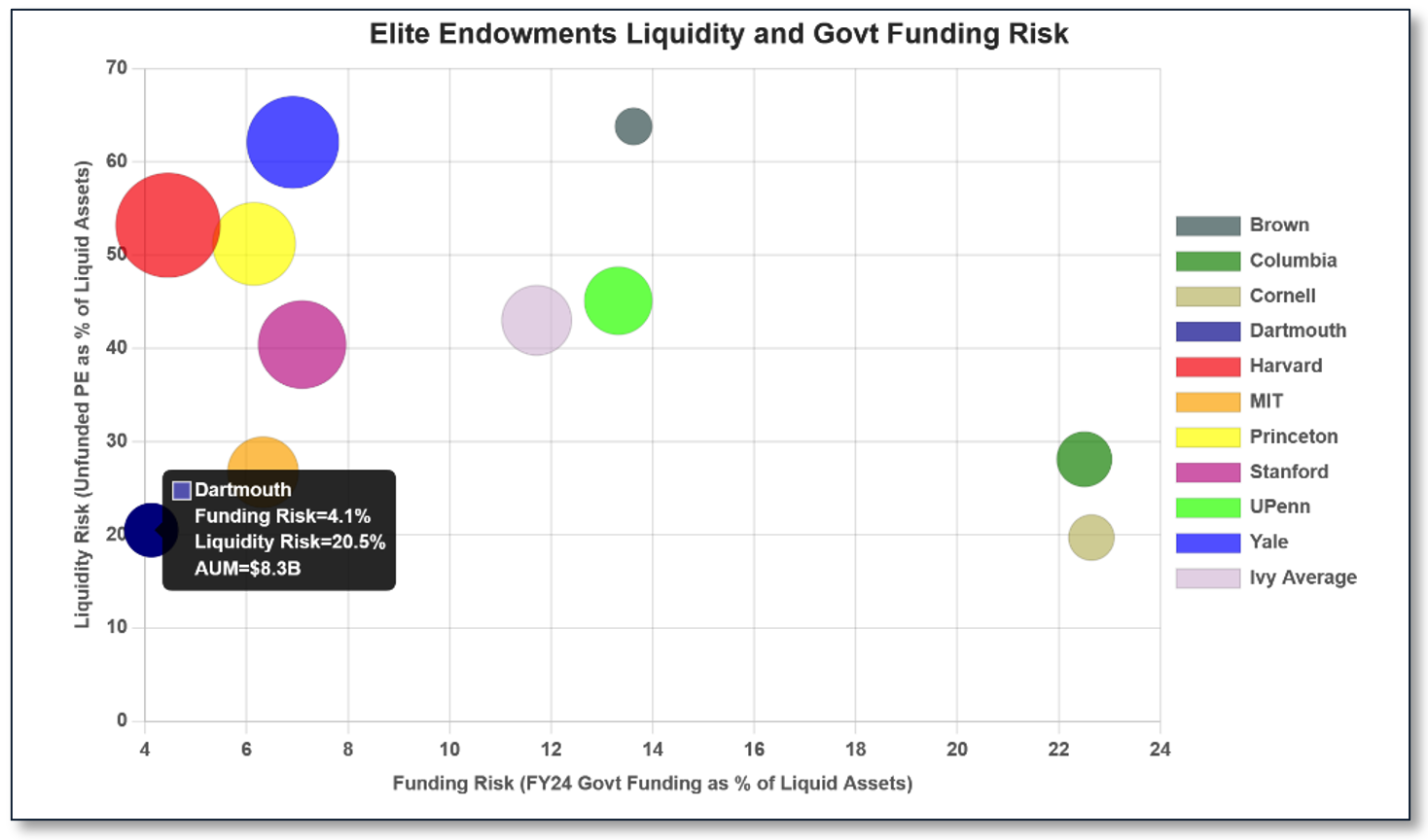

In the Elite Endowment Liquidity Stress Map FY24 below, we plot MPI-estimated PE allocations as a percentage of total assets (Y-axis) and the proportion of unfunded PE commitments to the sum of total allocated and committed PE dollar values (X-axis).

The X-axis ratio is a useful proxy for the vintage age of a PE portfolio. All else equal, the higher the ratio, the younger the portfolio. For a newly formed PE program, the ratio is 100 percent. After two years into a three-year investment period (with zero growth and distributions), it might fall to about 33 percent. Once the portfolio is fully allocated (years three to five, for example), the ratio approaches zero.

As the diagram shows, Dartmouth has by far the most mature vintage among elite schools’ PE portfolios. UPenn and Columbia, by contrast, have the least mature (by our admittedly rough estimates) and thus potentially lower probabilities of near-term PE distributions. Those distributions typically help investors fund capital calls on committed PE investments.

With the smallest unfunded commitments, a distribution-ready PE portfolio, and limited reliance on government support, Dartmouth stands out for its resilience — and offers a best-case blueprint for navigating today’s liquidity challenges.

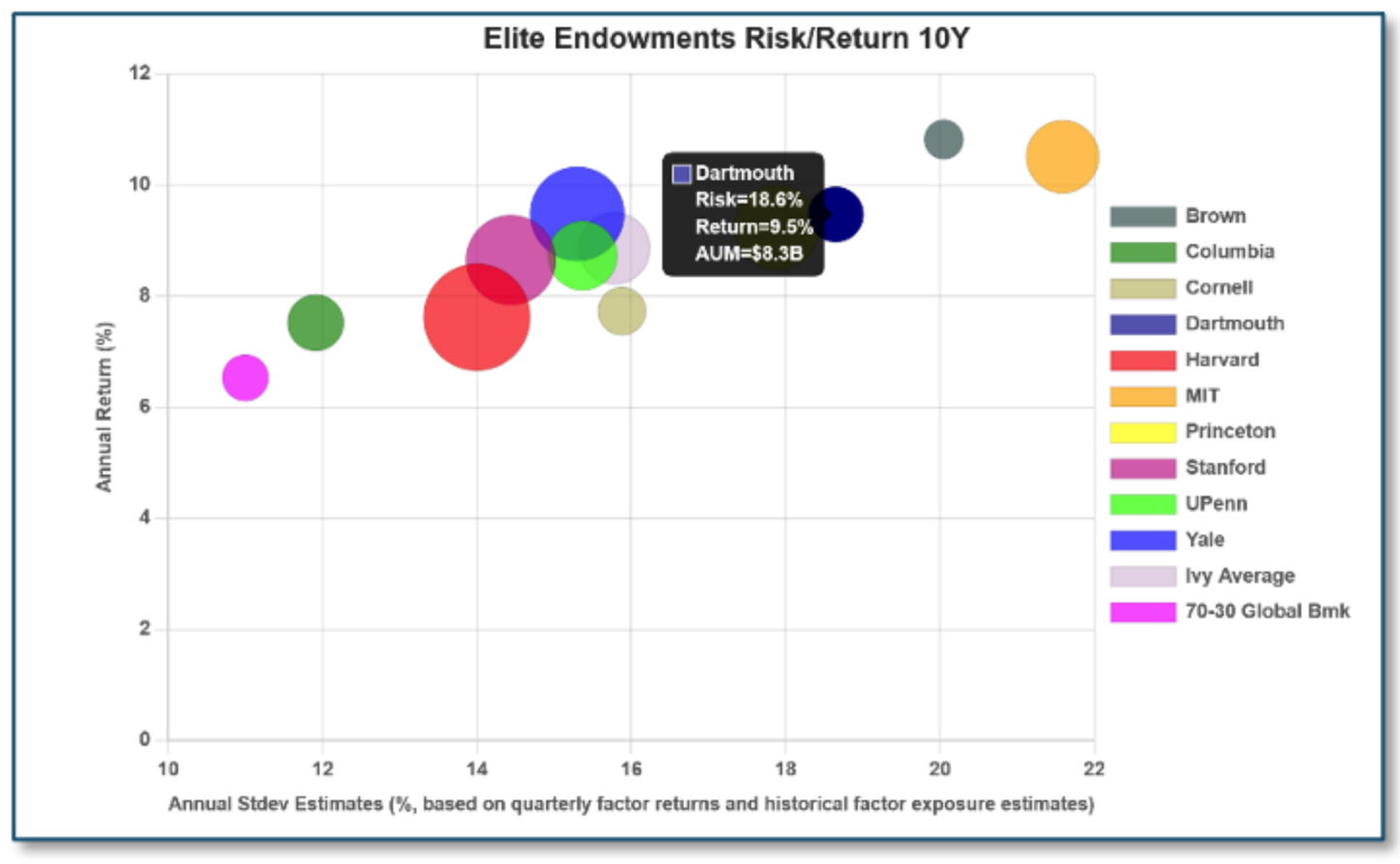

And not only that: the $8.3 billion endowment has delivered solid performance. Its 10-year annualized return of 9.5 percent matches Yale’s, albeit with higher risk (18.6 percent estimated annualized standard deviation versus 15.3 percent for Yale, per MPI estimates).

Among the ten elite schools in our diagram (including Stanford and MIT), Dartmouth trails only Brown and MIT in long-term performance — while taking significantly lower risk than those top performers.

Final Words

A public disclaimer is necessary: MPI has no proprietary information about Dartmouth’s investment portfolio and typically uses top-level public data — investment returns and financial statements — to reverse-engineer the inner workings of institutions (pensions, endowments, hedge funds, buyout funds). Dartmouth’s president, Sian Leah Beilock, and the endowment’s CIO, Alice Ruth, could provide more insight into the school’s remarkable achievement.

We can, however, offer thoughts on how they’ve done it. Intelligent cash-flow modeling and prudent pacing of private-investment commitments are key to responsible PE investing. Liquidity risks are more dangerous than market risks.

Michael Markov is co-founder and chairman of MPI.